Protest diary

Pip Harris shares her account of being arrested as part of the “LIFT THE BAN! Campaign" in support of Palestine Action.

Long read (14 mins)

I have been on many environmental and peace protests before, where I witnessed many an arrest. Often, it was in a ‘de-escalatory’ role. What I was feeling prompted to do here felt very different. I sat with the discernment for many days and talked to fellow Quakers, friends and family. In the final week I was certain I was being called to join those protesting, despite the potential consequences. I was expecting Parliament Square to be quiet, with upwards of a thousand people sitting and waiting with their pieces of cardboard and marker pens to start writing “I oppose genocide. I support Palestine Action”. It wasn’t quite like that. The action was well explained and a through briefing document and online sessions were provided by “Defend Our Juries”. Going up with friends Suzy and her daughter Doro who’d be acting as supporters, helped my nerves to stop jangling, and it was great to meet Rosalind whose name had come up in Wednesday's online briefing chat. Unsure what gender “Pip” was, Rosalind had spoken my name along the carriage, to be met with blank faces until she encountered us.

Happily, we found four seats together, close to Rosalind’s daughter, who was also prepared to be arrested. Goodness knows what any eavesdropping fellow passengers made of our conversation: how much water was sensible to drink, and by what time before our arrival at Paddington station; the merits and otherwise of Tena pads, burner phones, challenging crossword clues - and the difficulty of writing numbers in biro on arms and legs. Stepping out onto platform one at Paddington seemed all too familiar: almost a leisure trip. But we were on a mission with pads to fit, water bottles to fill and quickly lost track of time. When on our way to a prearranged meeting point, Doro alerted us to the fact that it was already 12:50, a rapid change of direction had us scrambling passed pro-abortion pro-life demonstrators. We approach Parliament Square with rising trepidation. The streets seem quiet: the odd police van and police standing on corners. Then we turned alongside Westminster Abbey and lines of police came into view, standing out clearly in their high vis jackets. Would we even get through to Parliament Square?

It was now 1.05pm. Susie held my hand tight, letting me know how proud she was of the action as we scuttled through the police lines, relieved to see the ‘Quakers for Peace’ and ‘Quaker Solidarity Palestine”. I hastily settled myself amongst Friends wearing similar blue “Quakers for Peace” T shirts and hurriedly scrawled the words on my sign. If I'd known that I was going to be still sitting six hours later, I might have taken a bit more time with the lettering. Nearby I recognised Kate, who held the Quaker banner. She smiled a familiar greeting and later came across to reassure me. That was calming as it was so noisy. So, so noisy. Loud music came from the pro-life demonstration on the other side of the square and it wasn’t until 5:45pm that I heard the familiar strike of Big Ben. I gathered my thoughts, shut my eyes and found a sense of calm, focusing on the grass in front and the Picasso dove image on the reverse of my placard. I glanced up occasionally at the brilliant posters, placards, and T shirts passing by; at the medics; at a statue now adorned with a scarf and holding a Palestine flag. It quickly became uncomfortable to sit upright. Close by, three other Quakers leant against each other's backs for comfort. I joined them and we formed four. As we quietly introduced ourselves, I heard the person on the far side being called ‘Louise’, but it was many minutes before I turned round to see that it was actually LOUISE! a Friend I know through the Quaker group “Restoring Relations”. I smiled to myself, recognising our shared calling: the extension of peace work, which starts with our relationships with others.

Arrests began, initially focusing on people in wheelchairs, then, soon, a person sitting next to me. We reached out to touch her back to form some kind of reassurance. On the other side of me, another Quaker ‘Steve’ also maintained a calm presence amidst the shouting and clapping crowd. We seemed to be on some kind of footpath, with photographers making their way past us towards the centre of the square and there was much noisy chat from supporters as they wandered through. I wonder if it would have been much more impactful if everyone could have been quieter. I returned to a gentle lowered gaze that helped me focus inwardly. Soon, I think, soon they must arrest us. We're right on the edge of the group. But no. Hours pass: gentle conversation between us, reassuring words and gestures from our supporters close by. Sharing of flapjack, water, fruit, dates, chocolate - I’ll be putting on weight just sitting here! Gentle enquiries of “Are we OK?”.

The Palestine march has arrived in the square and we presume that the police focus is elsewhere. Then we hear more arrests: a rush of maybe 15 officers surrounding and seizing people with shouts of “bubble, bubble!”, then “retreat!”. It feels faintly ridiculous - we aren’t running anywhere. The crowd shouts “Shame on you! shame on you!” at the police. Others cheer and clap. We hold our quiet gaze. Hours tick by: more snacks, a little chat. An older Quaker from north London is smartly dressed in a pinstripe suit - a genius move: he's asked many times if he's a lawyer. But no – this is an old work suit from years ago, his way of signalling that we are from all walks of life. When he needs to go, he leaves his sign with me, headed: “I oppose genocide I support Palestine Actions appeal in the High Court” with a simple paragraph of explanation. Further hours tick by. A group threads through the crowd singing protest songs. Then, after six hours of sitting I hear Big Ben chime 7pm: my deadline to get the train back to Devon. I decide to let it pass. I’ve stayed this long.

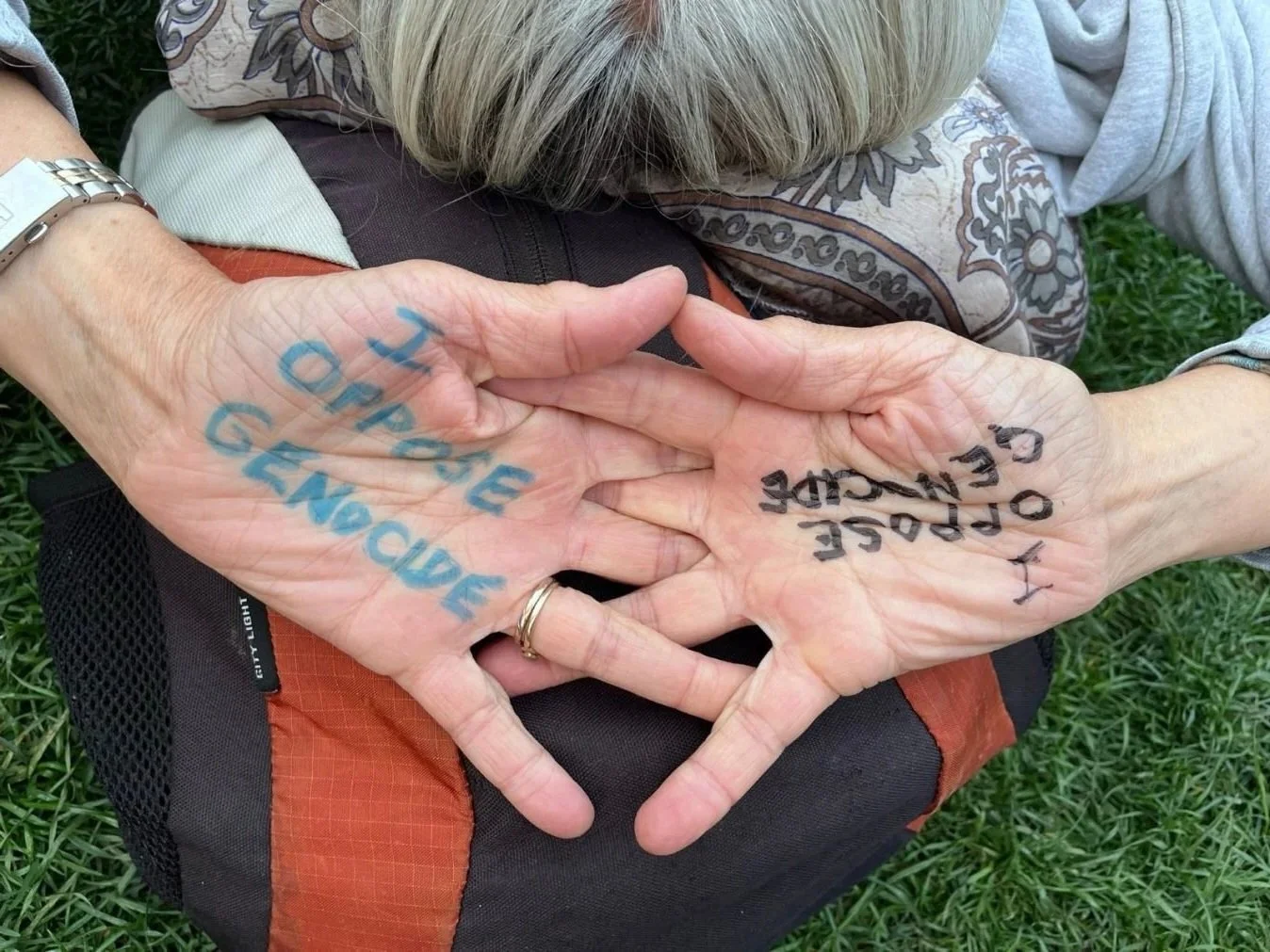

Familiar and unexpected faces appear: daughters of a neighbour who have been on the march. They express their surprise and appreciation. Even more heartening is the offer of a bed, whatever time of night I’m released. I could weep with gratitude, it helps to know I could have a refuge, when hours later I’m in custody and feeling pressured. We see more police amassing on the edge of the square. Arrests near us become more frequent, organized in teams of five or six officers to an arrest. Everything is calmer now, the crowd thinning out, the police finding their rhythm, and it's clear that soon we will be arrested. We decide to lie down, close together, linking arms and legs to make it more awkward for the police to surround us. I feel it is more difficult for those watching. On our own palms and each other's we write with marker pen “I OPPOSE GENOCIDE”. Suzy kneels down and asks “How shall we honour you? Celebrate you ... you know ... when you go?”. Laughing, she quickly adds: “no no - not at your funeral, when they ARREST you”.

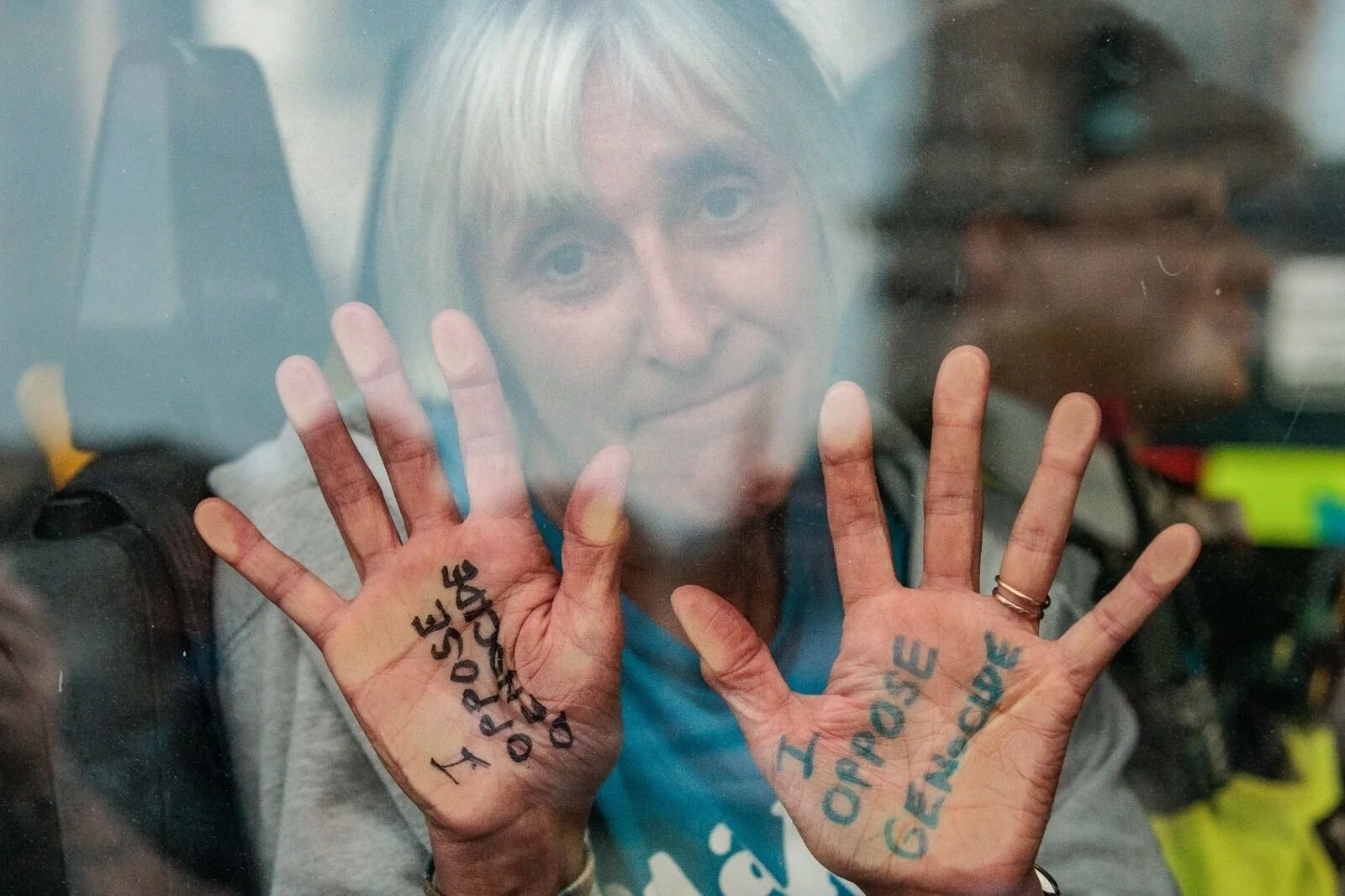

Then, suddenly, six officers are around me. A young police constable crouching by my ear I can hardly hear what she's saying. I nod, not quite sure what I've nodded to. She tells me the time of my arrest: 7.20pm. I focus on going limp, trying to let my head hang back as I'm carried aloft towards the vans. I hear cheers, clapping and shouts of ‘kick-ar$e Quakers’. None of the violence mentioned in the papers. The police are very respectful. They carry me between their vans and place me down gently. I'm briefly patted down. Asked “Am I feeling OK?”. I sit in the bus and realize I'm by the window ... I can place my hands on it and ... Wow! Gestures of thanks, love, appreciation, laughter. Cameras come out. Smiles ... The driver gets out to check what's written on my hands, then ignores me. My arresting officer looks away, not wanting photos taken. Later I have my palms photographed at the station.

Two more arrestees and their officers join us in the van. After maybe 15 minutes we set off on a circuit of Parliament Square, drive the length of the Parliament buildings, and find our way onto Millbank. In front of us is a temporary wall of solid white metal. We step out through the door to join a zigzag queue, a bit like an airport and see people stretching as far as we can see – maybe 800 meters, maybe more – along Millbank. We laugh nervously together... How long will this take? “9pm” suggests my officer. We quickly revise this to 10pm. We leave the zigzag barriers to form a new queue. Alongside that, a second one forms and then a third one. There's much hilarity. Who's pushing in? Very poor behaviour. No discipline!

Then we merge into a crowd. Wherever we look around us, police officers are holding bags and signs proudly declaring the banned message: “I Support Palestine Action”. A great photo-opportunity but alas, not possible. An elderly man (no names, of course, beyond “Spartacus”) recites Shylock's speech for me and explains why he's chosen the Merchant of Venice for his cell reading. He tells me of his wife, who was a Quaker when they met, and of his daughter, who has recently started attending meetings and gains a lot from this. A retired vicar smiles at me shyly. Later we share an inability to hold a tune as we attempt to sing “We will overcome” in a small, impromptu choir.

I’m asked by my officer about Quakers: I talk about where Quakerism started and about our testimonies. Later, the retired vicar speaks eloquently about why we feel it’s important to be here, and to challenge the government’s decision; why the change in approach to juries troubles us so much. Around us young men are being carried, tying up four police officers each as they refuse to walk along Millbank in the shuffling queue. A few arrestees sit out on the curb. A paramedic is on hand. We get to know the constables and their seniors: Met police from Bromley and Croydon. They clearly have strong bonds and a lot of affection for each other. It seems police catering hasn’t been good: one sandwich since they've come on duty at 10am. Meanwhile we’re allowed to share our remaining snacks with each other. They have clearly given up on regulations and hope it’s water, not vodka, we pass around. Together we laugh about the deadline disappearing.

By 10pm we've only inched slowly forward. There's a long, long stretch of people in front of us, so I am accompanied to the portaloos, past the white gazebos where they're processing people. The laminated sign “Prisoners’ toilets” jolts me a little. At around 11pm there’s a loudhailer announcement. Again, we're invited to provide our personal details: to consider telling people our name, address and date of birth, so we can then all go home! Several people decide to do this and form a large group on the other side of the barrier. We decline to join them, and this starts a guessing game with the police crew. What is my first name? Songs related to guesses develop. Eileen? Daisy? They settle on my name being “Rosalind”, although I have to keep being reminded of this. We move on to star signs to narrow down birthdays – Aries? Gemini? – then which counties we might come from, where the police stations we might be taken to, perhaps outside London? My arresting officer hopes the custody suite will be in Devon. She likes Devon. I resist a smile, keeping a straight face – they’ve decided I've come from Dorset. Our queue remains stationary as the many people street-bailed move forward to be processed first. Our police question the logic. Thank goodness it's dry and warm. We’ve been standing for nearly five hours now. The moon has moved out from behind the plane trees, across the gap of sky, then out of sight behind the buildings. Through the trees we catch sight of Lambeth bridge, lit up. The vicar states firmly: “this is where we need to be”.

Finally, we reach the black gazebo. A milestone where we collect an arrestee number, mine being 690. So, I'm the 690th person arrested – quite a result. It is now well past midnight. Before long we get to the white tents and my first grumpy reception from the Met officers seated there. My “no comment” is met by a very disgruntled officer who tries to convince me to take street bail. Meanwhile, my arresting constable is very amused by the contents of my bag. Amidst the triumph of finding a bus pass with my name, she compliments me on my well-hidden bank card (rolled up in my spare pair of knickers!) But despite knowing I'm called ‘Philippa Harris’, live in Devon, and started up my rail journey at Newton Abbot, they can't find out where I live. My constable prompts them to try phoning the bank. After they’ve tried three times, I understand their reluctance – no one’s answering the phone. Relief! It's a Monzo card! Normally I'd be distraught but this time I'm ecstatic. Despite the offer of a bed, I’m keen to prolong the process and help block up the system.

At last I'm allowed to proceed, to be taken into police custody at a station. We walk past the “prisoners’ toilets” to a custody reception – a line of plastic seats under another gazebo near the bridge. The two prisoners ahead of me are directed through a door, chosen apparently on account of their “great choice of reading material”. The constable directing them is clearly having too much fun. At this point it must be around 1.30am. I explain that my book is a short story by Alan Bennett... Hmm, he's not thrilled but allows me to exit through the door to a second “Pixie” van. This is Pixie 26, one of maybe 20, maybe 30 vans we drive past later, each with two or three prisoners and their attendant officers. Although we become very familiar with our Pixie over the next two hours, no one can tell me where the name comes from. My fellow prisoner draws the short straw of being seated in the metal cage at the back, with no cushions and an uncomfortable narrow metal seat. Luckier, I manage to doze off to the lullaby of radios messaging numbers, locations and apologies. There's talk of shifts being cancelled, of how officers are going to get home. Every police cell in Greater London is full. So “Yes,” they agree, tongue in cheek. “It's all fine. The Met Police are not in any way overwhelmed. There would appear to be zero places in any cell in Greater London, but no, no, it's all fine. No need to worry, just a few additional resources from Lancashire, Wales, Somerset, Derbyshire... But the Met can cope perfectly well.”

At last, a message comes through of space... We're on the road, driving past lines of parked-up Pixies, feeling some relief as we pull in alongside Hammersmith Police Station. Curious relief in a prison van, at gone 3am in the morning. We’re asked not to talk to the assembled group of supporters outside. Big metal security gates are opened. We cross the internal courtyard to stand patiently outside an anonymous metal door. Finally, we enter a corridor and my arresting constable sits in the holding cell with me. We chat for ten minutes, talking about her police career and how her police station differs from this one. Her superior officer leans against the wall outside and joins in. After a while, he points out that it's not usual for the arresting officer to sit with the prisoner in the cell. She maintains she wouldn't usually want to sit with a prisoner, but she trusts me. Her feet hurt in their unyielding heavy boots, and it's giving her a bit of a rest. She explains that the next stage is a more thorough search, down to turning my socks inside out, but still very respectful. She is concerned about my watch and jewellery. That complete, we at last reach the custody desk.

A tired police constable with a thick cold and a Yorkshire accent, calm and slightly amused, lists the contents of my bag. We play a version of “Kim’s game” about what we remember is inside: the two coats, the blankets, the water bottle, the coffee cup, the snacks, the money, the card, the sewing kit. “So well prepared!” they remark as things go into plastic bags – and then come out again as they realise everything should go into one. My constable helpfully prompts me that my mobile phone battery is flat. I try not to smile at this subtle collaboration. I roll up my sleeves to look at the numbers on my arms but there's no need – it's another guessing game. “Let me guess,” says the custody officer. “It’s ‘Alex in back office’ as your personal call, and the legal representatives are HJ&A”. The only thing that trips them up is trying to find out the post code for Parliament Square. Next comes identification. Again, a kind officer. I sit in front of the camera turning right, turning left. Gosh, I really am being profiled – a good one, thanks to Dad’s nose. Then the fingerprints, which take a while. First my fingers are gently rolled against glass then my palms, bearing their marker pen message, are pressed more firmly against it. A clever machine I'd like to know more about. I'm offered water, and then more water, and finally I’m led to my cell.

The harsh lights and clank of the cell door come as a bit of a shock but there's a loo tucked round the corner – bliss! I've asked for a blanket and that's stuffed through the door slot. It must be nearly 5am. Having rejected Alan’s Bennett’s short story for a battered copy of Quaker Faith and Practice as my one “allowed book”, I start to read “Chapter 24: Our Peace Testimony”. Soon, though, I feel sleepy. I pull the blanket over me – quite rough material but it blocks out the harsh strip lighting – and manage to sleep quite deeply. Noises awaken me. Before long, the little metal window opens and tea is offered. I read more of my chapter, many entries making me tearful – particularly an account written by a woman who participated in the 1980s vigil against the cruise missile base at Greenham Common. An action inspired and sustained by women. I re-read the final entry several times:

24.60 The first Friends had an apocalyptic vision of the world transformed by Christ and they set about to make it come true. The present generation of Quakers shares this conviction of the power of the spirit, but it is doubtful whether it will transform the world in our lifetime, or in that of our children or children’s children. For us it is not so important when the perfect world will be achieved or what it will be like. What matters is living our lives in the power of love and not worrying too much about the results. In doing this, the means become part of the end. Hence we lose the sense of helplessness and futility in the face of the world’s crushing problems. We also lose the craving for success, always focusing on the goal to the exclusion of the way of getting there. We must literally not take too much thought for the morrow but throw ourselves whole-heartedly into the present. That is the beauty of the way of love; it cannot be planned and its end cannot be foretold. - Wolf Mendl, 1974

The door lock rattles, and a smiling officer announces happily that he’s here to release me on bail. All is carefully explained back at the desk, where my belongings are methodically returned to me. There will be no interview, I’ll have to come back for that. I’m bailed to return on November 17th at 2pm. Finally, I’m escorted past the holding cells to a lovely reception from a team sitting on the pavement outside. They’ve taken turns to be here all night, patiently waiting to help us. Homemade cakes and coffee. Logging onto the system to let them know I'm released. Messaging friends and family. Finally, just after 8am, 20 hours after I first sat down with my placard, I set off towards the conveniently nearby Paddington station. As I walk along the street towards the tube entrance, I have a sense of a crowd of unseen friends and family walking alongside me. I glance down – the words “I oppose genocide” are still strong on my palms.

“It was love not hate that called me”, spoken by one of the Filton 18 protesters

I dedicate this account to Doro, and the many other young people who support us, dreaming of a fairer and more equal world. They would risk too much if they were to be arrested, so we gladly do this on their behalf.

Pip Harris. Quaker. September 2025